Joshua Teoh discusses a landmark case on patent infringement for variants.

In

Actavis UK Limited and others v Eli Lilly and Company [2017] UKSC 48, the United Kingdom Supreme Court (“UKSC”) upended patent infringement law.

WHAT IS PEMETREXED?

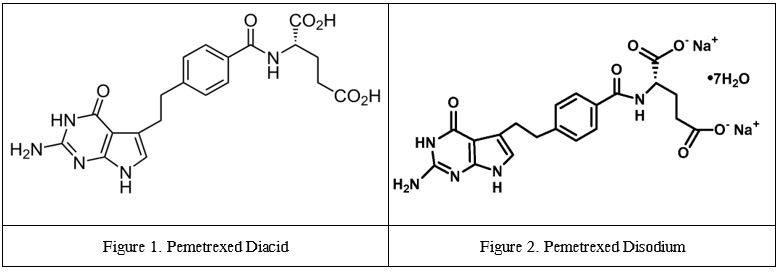

The dispute related to pharmaceutical compositions comprising pemetrexed-based compounds. Pemetrexed is a type of ‘antifolate’ medication. Pemetrexed has been known to have therapeutic effect on cancerous tumours, but with damaging and sometimes fatal side-effects.

Pemetrexed, when combined with two units of the carboxyl group (–CO

2H), forms

pemetrexed diacid. When pemetrexed diacid is dissolved in water, hydrogen (H) from the two –CO

2H units separate from the rest of the molecule to form protons; the remainder, which is the main molecule of interest, results in a pemetrexed anion.

ELI LILLY’S PATENT

Eli Lilly owned a patent entitled “

Combination containing an antifolate and methylmalonic acid lowering agent” (“Patent”). The Patent primarily claimed the use of

pemetrexed disodium in combination with Vitamin B12, and optionally folic acid, in medicament for cancer treatment. Pivotally, the Patent disclosed that the damaging side-effects of pemetrexed can be avoided if administered with Vitamin B12. Such medicament was successfully launched by Eli Lilly as ‘ALIMTA’ in 2004.

A key point is that when pemetrexed disodium dissolves in water, the two sodium units separate from the rest of the molecule to form protons, and the remainder molecule of interest becomes a pemetrexed anion. If this sounds familiar, it is because the structure of

pemetrexed disodium is just like

pemetrexed diacid, except that the former contains two –CO

2Na units instead of two –CO

2H units. Dissolving both in water results in two components: pemetrexed anions and a counter-ion (of sodium or hydrogen).

THE ACTAVIS PRODUCTS

THE ACTAVIS PRODUCTS

Actavis’s products involved other pemetrexed compounds used with Vitamin B12 for cancer treatment. Instead of

pemetrexed disodium, Actavis used

pemetrexed diacid or variants of pemetrexed containing tromethamine or potassium units (“the Actavis Products”). Actavis contended that as the Patent’s monopoly extended only to pemetrexed disodium, the Actavis Products did not infringe the Patent.

Eli Lilly claimed that there was direct and indirect infringement; direct infringement as the Patent covered all salt variants and the person ordinarily skilled in the art would conduct routine tests to establish which salt performed the same function, and indirect infringement because once sodium ions are added to the Actavis Products by medical practitioners, pemetrexed disodium would be involved in the preparation of those products.

The High Court found that none of the Actavis Products directly or indirectly infringed the Patent. On appeal, the UK Court of Appeal held that there was indirect infringement, but no direct infringement.

The issues before the UKSC were: (i) What is the correct approach to interpret patent claims and assess infringement in light of the Protocol on Interpretation of Article 69 of the European Patent Convention (“Protocol”) in relation to ‘equivalents’; and (ii) To what extent can a patent’s prosecution history (e.g. papers submitted from filing to grant) be used to determine the scope of the patent’s claims.

DEALING WITH A VARIANT

A ‘variant’ is a feature which differs from the primary, literal, or clear contextual meaning of a claim. Previously, the UK House of Lords formulated the landmark three-step “Improver Questions” in

Improver Corpn v Remington Consumer Products Ltd [1990] FSR 181 as to whether a variant infringes:

Q.1 Does the variant have a material effect upon the way the invention works? If yes, the variant is outside the claim. If no, then Q.2.

Q.2 Would this (variant having no material effect) have been obvious at the date of publication of the patent to a reader skilled in the art? If no, the variant is outside the claim. If yes, then Q.3.

Q.3 Would the reader skilled in the art nevertheless have understood from the language of the claim that the patentee intended that strict compliance with the primary meaning was an essential requirement of the invention? If yes, the variant is outside the claim. If no, the variant infringes.

Under the Improver Questions, if one were able to arrive at a negative answer to the last question, Q.3, this was taken to mean that the patent (or a particular claim under the patent) covers a class of things which included the variant as well as its literal meaning – with the latter being perhaps the most perfect, best-known, or striking example of the class. Arriving at a negative answer to Q.3 therefore would mean the variant infringes.

Fast forward 27 years, the UKSC has now criticised the Improver Questions. Q.1 required focus on “the problem underlying the invention”, “the inventive core”, or “the inventive concept”. Q.2 imposed too high a burden on the patentee. In respect of Q.3: (i) although the “language of the claim” is important, Q.3 does not exclude the patent specification and all the knowledge and expertise which the notional addressee is assumed to have; (ii) the fact that the language of the claim does not on any sensible reading cover the variant is not enough to justify holding that the patentee does not satisfy Q.3; (iii) it is appropriate to ask whether the component at issue is an ‘essential’ part of the invention, but that is not the same thing as asking if it is an ‘essential’ part of the overall product or process of which the inventive concept is part; and (iv) when one is considering a variant which would have been obvious at the date of infringement rather than at the priority date, it is necessary to imbue the notional addressee with rather more information than he may have had at the priority date.

The UKSC observed that an assessment on infringement must consider two distinct issues, best approached through the eyes of the notional addressee of the patent, also known as the person skilled in the art. If the answer to either issue is a ‘yes’, the variant infringes.

I.1 Does the variant infringe any of the claims as a matter of normal, purposive interpretation?

I.2 Does the variant nonetheless infringe because it varies from the invention in a way which is immaterial, based on facts and evidence?

The UKSC held that both these issues cannot be conflated as a single issue/question on interpretation as this could lead to wrong results in patent infringement cases. A key point here is that I.2 involves identifying the contextual meaning of the claim, and how extensive is the scope allowed for protection. I.2 also suggests the inclusion of the principle of equivalents, limited to inessential variants.

REFORMULATING THE IMPROVER QUESTIONS

The UKSC considered that it would be better to ask whether, on being told what the variant does, the notional addressee would consider it obvious that it achieved substantially the same result in substantially the same way as the invention. This question assumes that the notional addressee knows that the variant works and that it could apply to variants which rely on or are based on developments that have occurred after the priority date.

Accordingly, the UKSC reformulated the Improver Questions (“Reformulated Questions”) as:

RQ.1 Notwithstanding that is it not within the literal meaning of the relevant claim(s) of the patent, does the variant achieve substantially the same result in substantially the same way as the invention, i.e. the inventive concept revealed by the patent? If no, the variant does not infringe.

RQ.2 Would it be obvious to the person skilled in the art, reading the patent at the priority date, but knowing that the variant achieves substantially the same result as the invention, that it does so in substantially the same way as the invention? If no, the variant does not infringe.

RQ.3 Would such a reader of the patent have concluded that the patentee nonetheless intended that strict compliance with the literal meaning of the relevant claim(s) of the patent was an essential requirement of the invention? If yes, the variant does not infringe.

DID THE ACTAVIS PRODUCTS INFRINGE?

Using a normal, purposive interpretation, the Actavis Products did not infringe the Patent as no sensible interpretation of ‘pemetrexed disodium’ would include pemetrexed diacid, pemetrexed ditromethamine, or pemetrexed dipotassium. However, if one filtered it through the Reformulated Questions, the Actavis Products worked in the same way as the invention specified in the Patent, as they were medicament containing pemetrexed anion and vitamin B12.

RQ.1 was answered ‘yes’ as the Actavis Products achieve substantially the same result in substantially the same way as the invention. As for RQ.2, the UKSC found that the notional addressee of the Patent would appreciate that each of the Actavis Products would work the same way as pemetrexed disodium when included in a medicament with Vitamin B12. Factually, as at the priority date, the notional addressee would know that the use of a free acid worked as well as ditromethamine and dipotassium salts and would investigate whether pemetrexed free acid, pemetrexed ditromethamine, or pemetrexed dipotassium function in the same manner as a purely routine exercise. As for RQ.3, the UKSC found that even though the claims in the Patent call for pemetrexed disodium, there was no plausible reason why any rational patentee would limit the scope of protection afforded by the Patent to only pemetrexed disodium, as the Patent specification stated that other antifolate drugs have similar effects as pemetrexed disodium.

Accordingly, the Actavis Products with pemetrexed were found to directly and indirectly infringe the Patent in the UK and also in France, Italy, and Spain.

REFERENCE TO PROSECUTION HISTORY?

The UKSC held that reference to the prosecution history would only be appropriate where the point was truly unclear and the contents of the file would unambiguously resolve the point, or where the patentee had earlier decisively stated that the scope of the patent did not include the sort of variant now claimed as infringing.

CONCLUSION

Besides reformulating the Improver Questions in considering whether a working variant varies from the invention in a way which is immaterial, the UKSC appears to have also introduced a new two-part test (through I.1 and I.2) for considering whether an alleged variant would infringe a patent claim. This two-part test provides that determining patent claim scope was not solely a construction issue as only the first part was claim construction. There is infringement if the answer is ‘yes’ to either issue.

For the second part of the test, although the Reformulated Questions are meant to be guidelines, their application would seem to extend the scope of the claim to include all immaterial variants that work as prior to this, it is limited to only immaterial variants that were known as of the priority date. Therefore, one could now argue that any immaterial variant which achieves substantially the same result as the patent invention and in substantially the same way will amount to infringement.

It must be noted however that in this case, the UKSC had only considered the Patent on issues of patent infringement for variants. There was no, or minimal, consideration of the validity of the Patent and the impact of the extended broad scope of claim upon the validity of the Patent. One could therefore argue that this decision is meant for a context where the issue of whether a variant is infringing is concerned.

Whilst the courts in Malaysia have referred and applied the purposive construction and the Improver Questions for patent infringement, it remains to be seen whether the courts would follow this recent UKSC decision in dealing with a variant, particularly given the possible influence of the requirements of the Protocol, a parallel which does not exist here.